"We can speak frankly now," said his father, admiring the smattering of possessions as though it were a conquest instead of a gift. "Though I know none of this changes anything for you. You would rather have nothing and still live in the garrison like a stableboy."

The boy merely looked at him. How old he seemed, then, in that moment, Sigismund. Suddenly gray in his whiskers with little crevices in his face. Yet the same as ever. Free as a vulture, his uncle once said of him, and just as tethered to death. His age reminded Siegfried of the moths that would dance around the night fires during Shrovetide. The Shrovetide fires were so big that moths by the dozens abounded, as there was no other light at night save for the moon.

"I loved your mother," said Sigismund very suddenly. "No one knew that but her."

At first startled by the confession, the boy then shook his head, his eyes cast down.

"She didn’t love you."

"I know. But sometimes it felt as though she did. It’s something I don’t think a boy of your age could possibly understand, what happened between me and her. And I know that you don’t love me either. In the end, it matters little. Here you are, together, with me. You know, I’ve been keeping an eye on you, all the while. I watch you train sometimes from the mezzanine. Do you know what I noticed right away?"

"What?"

"You count when you fight. It’s how you stay so steady, so rhythmical when others falter. It keeps you calm."

Siegfried faltered. "How do you know that?"

"Your mouth moves. You count in Slavic. Ena, dva, tri, štiri, from there on who knows. I do it to. I also count. You can do sums, too, can’t you? All in your head."

"Yes," said Siegfried quietly.

"And you have the gift of two languages."

"Yes."

"And you are brave, like your mother. You, better than anyone, know how brave she was."

"I do," said the boy, fighting back tears at the thought.

Sigismund knelt down to look closer at his son. He had never before been so physically close to him. He reached out and brushed a lock of curly blond hair away from the boy’s forehead. For the first time, the boy let him. Gentleness looked wrong on the steward's face, contorted it in a way it wasn't made for.

"You look like her. You have her eyes. I remember thinking that the first time I saw you. Every year, I would see you, out in the fields. I recognized you and you never once recognized me…"

At this, Siegfried turned away from his father and said nothing.

After they parted, he returned to the stables, where dinner was waiting. And in the stables Siegfried stayed, with - after some negotiations between the marshal, the steward, and the boy - the exception of Sundays.

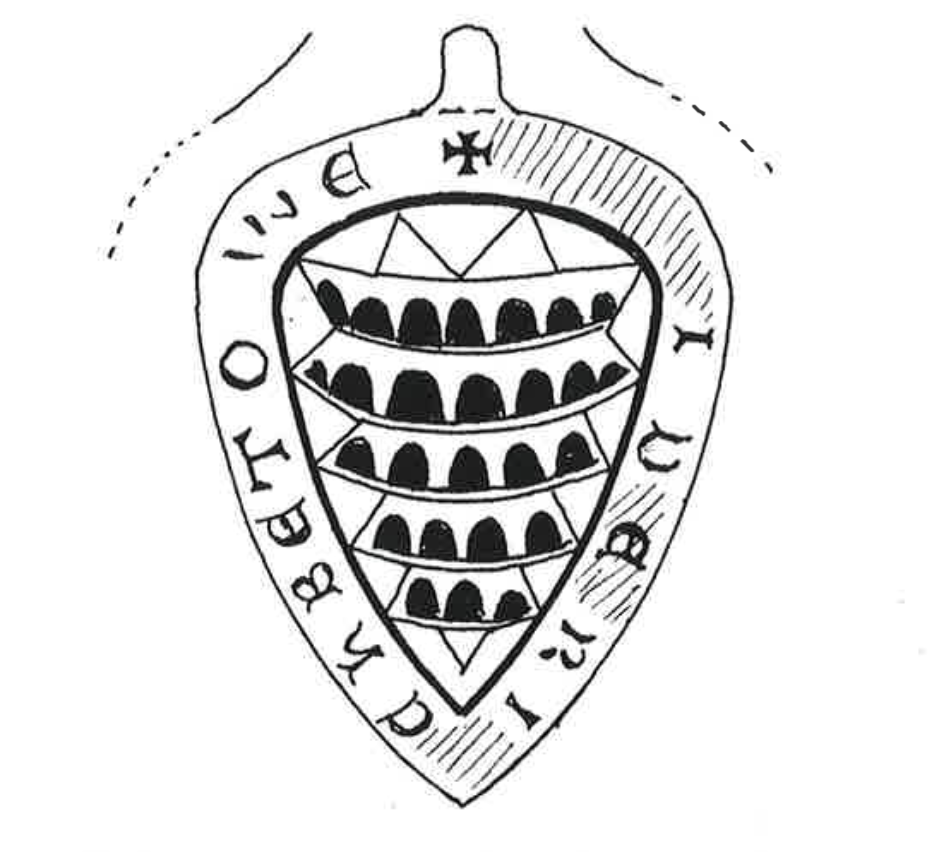

Thus, the world of the castle was opened up to Siegfried for the first time. It was one thing to be in the stables or the courtyard, but inside the castle was another matter altogether. It was a strange castle, Siegfried always thought. Atop its bald hill, it could be seen for miles in every direction. A jagged horseshoe in plan, penetrated in one of its bends by a tall, crenelated tower. Another tower to the west, one being built to the on the side of the hill facing the orchard. And yet when he got nearer and nearer to the castle, it didn’t seem as big as it did from afar. Castles in stories had full tilting fields, grand stables, a hundred rooms. Pettau had a small courtyard with a well in it.

Siegfried had only been in the kitchen, and, of course the storeroom where he saw his mother with the steward on that awful day. And later the steward’s quarters in the eastern wing, where the other household staff lived and which had a separate entrance. But he’d heard lurid details about the castle before, details which captivated him as a younger boy. His uncle had once gone up to visit the lord to ask for leniency on some debts owed due to a bad harvest. The great hall, he said, was like a forest of stone pillars and arches, with windows carved out in the high part of the wall. And the lord sitting in his chair before a roaring hearth, a long table in the center of the room, sofas along the walls where visitors and soldiers played games and women embroidered by windowlight. And everything in there was rich beyond measure. No one was ever cold.

"What was the lord like?" Asked Siegfried.

"He wasn’t much interested in ordinary people. He had a warlike face with thick, bushy eyebrows. He forgave me my debt but only because he had other things on his mind. I don’t think he looked at me a single time. Other people from the villages were there too. Stribor, a kinsman of our neighbor, who lived on the far periphery had his house burned down by the Hungarians and was asking the lord for compensation."

"And what did the lord do?"

"The lord had the steward give him some money and Stribor asked, what am I to do with this? How do I feed my family with this? But the lord was agitated by this question. I don’t think he knew the answer. Money in those days was new and only had worth to the people in the towns and the nobility. We survived on the currency of bread. He couldn’t grasp this."

"And then what happened?"

"I don’t know. Stribor rebuilt his house further away from the border, and it almost starved his family that winter. He lost the good soil that was inland from the Drava marshes. All such soil further downstream belonged to other families. He settled somewhere near Kostanj hill so he could see the Hungarians coming. I understand his bitterness. We pay the steward tithes in exchange for protection. And all this business between Frederick and the Magyars only put us further in harm’s way. Half my life it’s been going on, and never seems to get better."

"But why are they fighting?"

"Why does any nobleman fight? Over land and its riches."

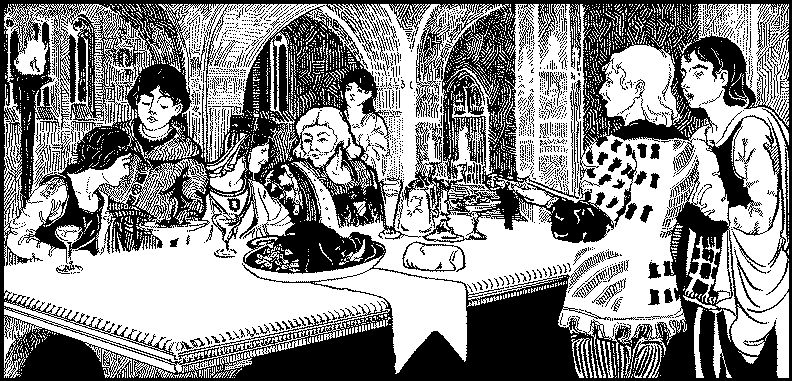

The inside of the great hall was as Bodin described it. The forest of arches and columns. Siegfried tried his best to be unimpressed, but the sheer finery of everything alighted his senses. The walls were brightly limed, the floor clay-tiled. From one of the barrel vaults hung a chandelier to be used during feast days, and on the long, dark wood table, four candelabras. The hearth burned endlessly with little care for the expenditure of firewood, illuminating the entire room. Every evening, Sigismund went to the castle to eat with the lady, as did Ermenrich, his wife Frija, and Walther. There Siegfried formally met not only the elusive lady, Frederick, and Henry, but discovered for the first time the full extent of the late lord’s family.

The inside of the great hall was as Bodin described it. The forest of arches and columns. Siegfried tried his best to be unimpressed, but the sheer finery of everything alighted his senses. The walls were brightly limed, the floor clay-tiled. From one of the barrel vaults hung a chandelier to be used during feast days, and on the long, dark wood table, four candelabras. The hearth burned endlessly with little care for the expenditure of firewood, illuminating the entire room. Every evening, Sigismund went to the castle to eat with the lady, as did Ermenrich, his wife Frija, and Walther. There Siegfried formally met not only the elusive lady, Frederick, and Henry, but discovered for the first time the full extent of the late lord’s family.A daughter, Clothilde, Henry's twin sister, arrived with her brother hand in hand. A twin! It seemed like quite the omission on Walther's part when Henry was pointed out at the fight. (But then again, he thought, the girl was only a girl.) Siegfried found himself entranced by how identical the two Pettaus looked, their identical height, their identical hands, noses, mouths, boy and girl, each the inverse of the other and different from all. Then came the boy Arnold, twelve, and the youngest daughter, Benedicta, nine. None of them paid much attention to Siegfried when he first entered the hall with his father. The women were giving the servants directions, the men were huddled together in furtive conversation, the twins played chess while Arnold hovered over them, belt cutting into his rather round little belly. Shyly, Siegfried trailed Walther, who explained the last few strangers to his companion.

Seated next to Frederick was the chamberlain Faroald, freshly returned from Carinthia after some months. Siegfried had seen Faroald a handful of times, usually atop Alberich, a black horse Siegfried knew well, coming and going. Always in his mail and helmet, which looked funny on Faroald’s slight, skinny build. Without his helmet, Siegfried wondered if the Faroald on the horse and the Faroald sitting at the table were the same man. The man on the horse was severe and quick-moving. It startled the boy, then, how handsome the chamberlain appeared. Perhaps even beautiful. Long, swanlike neck, a well-cut jawline. Blue eyes, wide and limpid, straddling a perfect, upturned nose. A shaved, sweet mouth made Faroald appear more youthful than he was. But beneath his beauty there existed a sharp coldness, a quiet ruthlessness. "Cunning, like a fox," Walther, who disliked Faroald, said. "He does dirty work."

"Dirty work?" Asked Siegfried.

"When the lord, in his time, needed a village burned, a threat delivered, spying undertaken, it wasn’t my father nor Sigismund he sent. Your family down there in the fields fears the steward only because they know nothing about the chamberlain."

Siegfried didn’t believe his friend at all.

"A man who looks like that," he murmured.

"What, like a maiden’s corpse?"

They laughed.

"Well who is that, then? Next to him."

"Lothar. The cup-bearer. He’s been gone forever. He’s basically a second marshal. I told you about the vineyards in Holermus. The lord built Lothar a small tower, enough for arms and ten men to sleep in. He lives out there. He prefers it to Pettau. My mother calls Lothar the most unmarried man to ever walk the earth." This, admittedly, was a very funny thing to say, as the two boys stood by and watched Lothar wipe the wine off his bristly brown beard and, subsequently, his soiled hands on his cloak. Siegfried remembered the days in late August when the whole of the population stood by watching the barrels of wine roll in on large carts, the man who must have been Lothar leading them in, his horse tall and mean-looking. Walther told him that one of the cupbearer’s teeth had been knocked out in a brawl. This gave him a smile purpose-made to discomfort whoever was on the receiving end of it. Despite being such an ugly man, Lothar possessed a beautiful, deep voice. When he spoke, he captivated. It was said that when he sang, everyone fell silent.

As everyone gathered around the long table, servants brought out the food in practiced succession, like altar boys did the Host. The girls tittered to themselves; an attendant helped re-lace little Benedicta’s dress, much to the girl’s consternation. You always make it too tight! It took an eternity for the dinner to merely get started. So many rituals. Passing a bowl around in which one rinsed their hands, Henry, holding the bowl for his sister and she for him; Clothilde drying her brother's hands, and her brother her's, as though the two of them were entirely separate from the rest of the gathering. A lengthy prayer, said by the lady. The portioned serving of the food by servants, then the pouring of wine. All done with little talking. How long could getting ready to eat possibly take?

"Watch how everyone eats," murmured Sigismund to his son. "Don’t pick your teeth with your knife. Don’t wipe your hands on your clothes. Dab your mouth before you drink. Sit up straight. This isn’t a peasant dinner table. Or the stables."

Out of necessity, Siegfried paid great attention to the motion and chatter of everyone. They all seemed impossibly perfect to him, restrained, unfettered by hunger. Imagine eating slowly! Imagine not being smacked or scolded for taking more food! Imagine being served by a whole other person whose purpose it was! And the food overwhelmed him: bread made with white flour, ten roasted chickens, pickled vegetables, cooked apples with spices. And all just for an ordinary Sunday! Feast days, holidays, he couldn't imagine.

No, this was the other world from his uncle’s favorite story, the world that lied at the bottom of a great cave where everyone was beautiful and no one hungered. How could it have been, that every day his father ate like this while his mother made pottage from old barley and scraped the mold off of bread with a knife? Were it not for his tremendous hunger, the thought would have nauseated him, the thought of so much wealth, of his father not even feeding her well, the woman he allegedly loved. After a long while, after a year of creeping acceptance, those old thoughts again about where he came from. Thoughts he only had on harvest days, when he withdrew from the world from shame. Should I eat this food? What right do I have to it? And these people with their eyes all on me, looking at me like that, with curiosity and derision, knowing, as they do, what I am. God, how they must despise me! How little they must think of me! Even Lady Benedicta stares. Siegfried’s eyes drifted listlessly down to his lap.

"Did you notice, my lady? Sigismund has brought his son with him for the first time tonight," said Ermenrich, at what felt to Siegfried as the worst possible moment. At the head of the long table, Benedicta politely craned her neck.

"Look up, boy," muttered Sigismund.

"Ah, I see," said the lady, her voice warm and deep for a woman’s. And what is the boy’s name again? Forgive me for my forgetfulness. No, steward, do not speak. Let the boy introduce himself."

"Siegfried, my lady," said Siegfried, wondering why his voice came out so quiet and meek.

"Siegfried, yes. I remember now. Quite a name for a halfling, is it not? You are nothing if not ambitious, Sigismund. And young man, if I recall correctly, our marshal here is the one training you?"

"Yes, my lady."

"How goes he, Ermenrich?"

"I find him very gifted, my lady," the marshal said, to Siegfried’s simultaneous relief and embarrassment.

Benedicta steepled her fingers. "Oh? In what way?"

"He’s calm. Other boys are scared of the sword, but Siegfried here is very relaxed. Coming from where he does, he has more to prove. Also he’s especially good on a horse. You know, he’s been in the stables for a while, helping with the horses - yours included. But what most impresses me, my lady, is his cleverness. When he first came to me, he could barely speak any German. And now, despite a bit of stableboy vulgarity, he’s as good as any of the other children, if you can excuse him having a Slavic lisp. And the boy’s father says he can reckon well. The peasants taught him how to in the fields."

"Quite the eventful life you’ve lived already," said the lady, smiling. "This is good to hear, marshal, really. My late husband would have thought it a waste for someone like Sigismund to die without passing on his gifts. Bastard or not."

"Hence why I would like it, my lady," interjected Sigismund, if the boy could perhaps go north and someday become a squire there. Now that you have heard all this…"

Frederick gave his steward a withering glance.

"Is this really an appropriate request to be made at dinner?"

"Forgive me, then," said Sigismund quickly. It pleased the steward’s bastard immensely to see his father talked down to.

"But," continued Frederick, "You know, I may soon be married and there could be a place for him there with my in-laws."

Sigismund’s head perked up like a dog’s. Evidently this was news to him.

"Married, my lord? May I ask further?"

"It makes sense that my mother wouldn’t tell you, though I suppose it is your concern. We are in talks with the Unterdrauburgs, you know, who keep watch over the Jauntal."

"Ducal ministerials?" Faroald chimed in, interest piqued.

"Yes, but if Adalbert has his way, the children would belong to Salzburg."

"Then, forgive me, what is the point, my lord?"

"Adalbert is the Archbishop, right?" Whispered Siegfried. Sigismund nodded.

"Regardless of whether this is the way out from under Salzburg, the Unterdrauburgs are part of the Trixen clan. Their lot owns half of South Styria. Most of everything along the Drau. Rainbert of Mureck, son of my uncle's friend, a kinsman of the Unterdrauburgs and their kinsmen Gottfried of Trixen, Kolo of Saldenhofen, and Alfred of Mahrenberg, all served squire beside me in Graz. We have become very close. We took our crusading vows together. It would be nice to become closer in what I think you would agree are uncertain times. In other words, Faroald, I want to start playing bigger games. And I didn’t ask for your counsel."

It occurred to Siegfried then that he’d been let in on the type of conversation very few people were allowed to hear. Everyone at the table began looking at one another uneasily. Frederick talked like a man twice his age. His years up north must have given him a certain confidence.

"Bigger games? My lord should remember that he is not yet knighted. You haven’t told me the full extent of what your doings in Graz, but I should remind you that here, in Pettau, your father left you on bad terms with Salzburg, what with the tower building on the border and the feud he waged with the Weitings up in the Lungau."

Frederick became animated, perching himself up on his fingertips.

"Let Adalbert pretend the border doesn’t interest him! Let him save face in front of Hungary. Like the Emperor who plays both sides, he knows as well as I do what benefit there is to moving the border East. In wine growing alone. He merely didn’t like the way my father chose to do it. But I am not my father. I spent lots of time in Graz with Duke Leopold when serving as a squire to the Ehrneggs, even though the duke is not my sovereign. Adalbert knew this, too. He allowed it because I took a crusading vow, and for the same reason, he’ll allow me to marry the Unterdrauburg girl when she comes of age, ducal ministerial or not.

"The political shift has changed things anyway. Things have calmed down between Emperor Barbarossa and Italy. The pope is dying, and as he gets closer to death, he becomes more concerned with his legacy in the Holy Land. King Baldwin's death was a blow, and his quarrelsome sons have led Jerusalem into war. Saladin's forces have wreaked havoc on Tiberias. It wouldn't surprise me if a crusade was called by the end of the decade just for the old man to save face. Many are already taking pleadges in anticipation, including myself. In that case, Barbarossa has every reason to reconcile with Hungary to ensure safe passage. Everyone is playing both sides, as I said."

"Who said that? About a crusade?" Asked Faroald.

"Duke Leopold, who also plans on taking up the cross and intends to profit otherwise from the truce."

"News to me."

"Well, that’s because you were in Carinthia all those months spying on Kunigunde and her husband."

"Who is Kunigunde?" Whispered Siegfried to Walther, who sat on the other side of him.

"Frederick’s elder sister. Remember?"

"How many Pettaus are there? How have I not seen Arnold before?"

"He’s at the Church of Saint George down the hill, living in the rectory with Ewald. He’ll take vows and serve as parish priest there. You wouldn’t like him anyway."

"And the girls?"

"Why would someone like you be allowed to see them?"

Siegfried fell silent.

"It’s a delicate situation," said Faroald, justifying himself. "Your father stole all that land near Mahrenberg for Kunigunde and Lantfrid of Eppenstein married into it. He's been in that nasty feud with his neighbors, as we already know, but now he's also thinking of leaving for the Holy Land, as atonement for the feud. If he should die in either conflict, or in a judicial duel, what do you think will happen?"

"Is this true, what you are saying to me?" Interrupted Benedicta, alarmed.

Faroald gave her a glance that said, this is why you all need me.

Frederick rested his hand on his palm. "Really, why does the land matter? It made for a cheap dowry. Would you rather us give something important of ours away?"

"There could be trouble over it if Lantfrid dies. They have no children."

"So let there be trouble," said Frederick. "When has this family ever been unprepared for trouble?"

"Steward, that child of yours sure is getting an earful tonight," smiled Ermenrich, a not so subtle warning. "By the way, my lady, I have a question for you, if I may."

"Yes, marshal."

"Henry leaves quite soon for Gurkfeld, does he not? I was wondering what kind of entourage you wanted me to put together to see him there."

"Why is Henry going to Gurk?" Asked Siegfried, louder than he intended. Everyone fell silent and turned to look at him. He’d spoken out of turn.

"Henry is going into the clergy," explained Ermenrich politely. "He’s learned all he can at St. George's and will live with the Bishop in Gurk so as to be trained in chancellery. Oh, you don’t know what that means. He’s going to become learned. Maybe a bishop himself one day."

"I can speak for myself," said Henry. His sister reached to brush the hair out of his eyes, but he stayed her hand.

"Can you?" Teased Arnold, looking directly at Clothilde, whose expression, Siegfried noticed, had turned hollow and grim. The girl said nothing, as though she didn't hear her brother's slight.

"Arnold," warned his mother. "Marshal, do what you see fit. Ten men, perhaps? Armed?"

"Ten is excessive, mother," Frederick said. "Five maybe, if armed."

"But your brother has never held a sword in his life. He cannot protect himself. And we are sending the Bishop many gifts, plus all of Henry’s things…"

"Fine, ten. It’s your money to spend."

The meal ended and the servants began clearing the table. Siegfried watched them, trying to discern whether they were Germans or Slavs, yet found this impossible to do without hearing them speak. What could he say about the dinner, he already wondered. Was he closer to the servants or to his father? His mere presence seemed as though was violating an invisible boundary. Eating that food, listening to that conversation. Is this what these people talked about? Money and land and marriages and people more important than them in faraway places? A shiver ran through him, not entirely out of disgust, but because he sensed that he was being stared at.

Indeed, from across the table little Benedicta peered through her dark eyelashes at Siegfried. Unlike Clothilde’s, her hair was as black as her namesake’s and hung pin straight down to her ribcage. By Siegfried’s reckoning she must have been born after her father died. Her stare was curious, yet idle. He knew she waited for him to speak to her, but Siegfried had nothing to say, nor the right to say it. The only bond he in this girl shared was that of similar age. He looked towards Walther for help, but his friend was engaged in a conversation with Arnold.

How was it possible to keep track of all of these people? He decided on a system of hair color. First there were blond Pettaus, Henry, Clothilde, Arnold. Then, there were black-haired Pettaus, Frederick, Otto, both Benedictas, though bearing so many children had aged the mother and upon closer inspection, her eyebrows were speckled with gray. Benedicta’s relatives were the Ehrneggs who were allegedly noble? And thus Frederick ended up somehow at the court of the Duke of Styria instead of with the Archbishop in Salzburg who was his sovereign?

"How come we don’t see you at St. George’s on Sunday, Siegfried?" Asked Clothilde, whose skin was so pale the blue of her veins showed through. "You really should come. Soon it will look so beautiful once the roof is finished. Or do you still go to peasant mass where they guzzle the host and roll on the floor?"

Arnold and Henry laughed with their sister. All three of them had the same perky button nose. Except Arnold was considerably more porcine in appearance than his twin siblings.

In spite of these words, especially since they came from the mouth of a woman, Siegfried calmed himself.

"Well, in truth, I hadn’t been invited until now. I should thank you for offering me your kindness."

Clothilde frowned, nose wrinkled like a pig. "That is not what I said."

"Forgive me, then. 'You really should come.' Were those not your words, my lady?"

Little Benedicta burst with laughter. "This boy has only just learned German and already he bests you in a game of words, Clothilde. Well, then, Siegfried, I hope we will see you next Sunday. You have at least earned a place through cleverness."

"Benedicta fancies a bastard," Arnold sniped, eyes turned to his older siblings, begging for approval, but they paid him no mind. Benedicta merely smiled.

"I accept the attention of anyone who is courtly towards me. If Sigismund is mother’s steward, I see no reason why Siegfried cannot be mine."

"Oh, look, you’ve turned his bastard face bright pink!"

Mortified, all Siegfried wanted in that moment was to leave. It was one thing when garrison boys did this to him, but the lord’s little sisters? When the servants finished clearing the table, he sighed deeply, believing his prayers to be answered.

"Are we leaving, father?" He still wasn't used to referring to the steward as 'father.'

Sigismund frowned. "Why would we leave? Frija is going to play the fiddle and Lothar will sing."

"Please, father, can’t I be allowed to go home? I have no right to talk to any of these people."

"But they have the right to talk to you. And you, Siegfried, have an obligation to be talked to."