Meanwhile, the Pettaus, their soldiers, and the town bourgeoisie, began attending mass in the unfinished structure. The first time Siegfried stepped into that great, vaulted room, the first time he saw the glittering stained glass casting light muted by the scaffolding outside across the broad tile floor, his breath caught in his throat. Nothing could be further from the wooden chapel in which his family crowded each Sunday, shoulder to shoulder with all the other families, even though none of them understood a whit of Latin. The parish priest Ewald said several masses on Sunday, including in the villages, but the first and most magnificent was at St. George’s. How could it be, that Ewald, this same frail man, who out of pity stopped via donkey by the little hovel churches of the peasantry, suddenly seemed so resplendent? Was it really that he merely wore newer vestments, and that that vast room carried his voice all the way to the heavens?

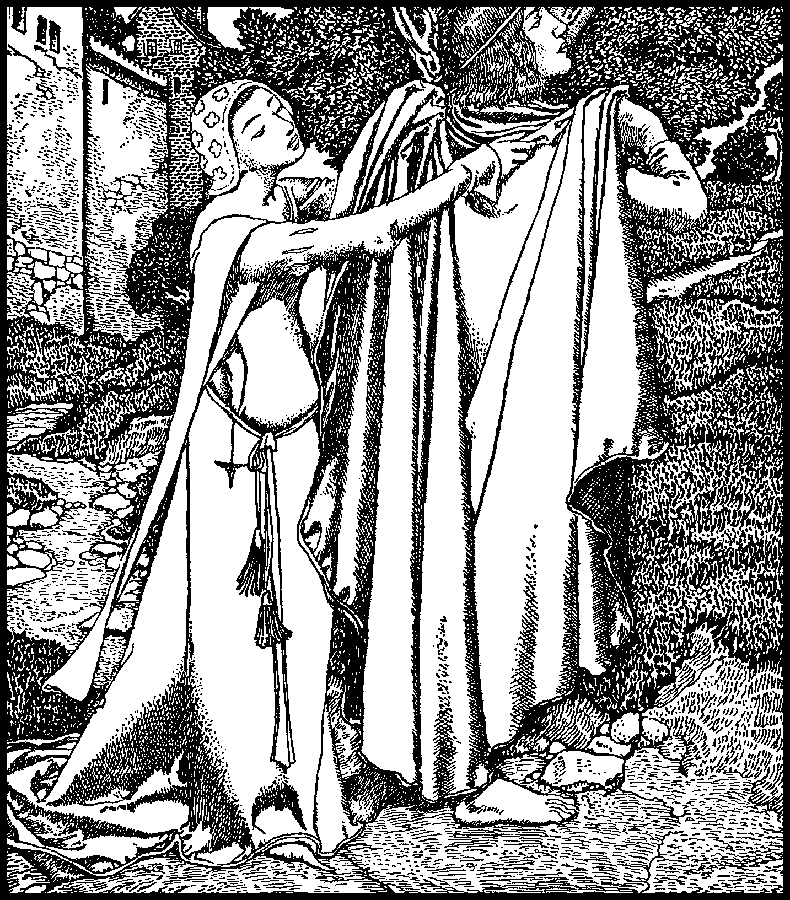

One by one the Pettaus walked in, dressed in utter finery. White silk shifts and veils for the girls and women, jewelry crowding their wrists and fingers. The men in their velvet mantles and scarlet surcoats. Frederick with his beautiful black hair, finely combed, the first emergences of stubble appearing on his young face. One by one, the women covered their heads as they entered the church. Lady Benedicta, her face white as the moon, chalcedony rosary clasped around her fingers. Clothilde, her hair in elaborate braids adorned with gold ribbon. Little Benedicta, with a single black pleat down her back, in true contrast to the pure white of her clothing. The women’s sleeves trailed down to the floor, and when their hands met in prayer the sleeves billowed like waterfalls into their laps.

Siegfried, dressed finer than he’d ever been before, kept teasing at the fur lining of his mantle, as though to make sure it was still real. During the mass, Henry and Arnold stood dutifully in vestments of their own, what, alter boys, now? reckoned Siegfried, who knew nothing of Catholic hierarchy beyond priest, bishop, archbishop, pope. When Siegfried received the Host on his tongue, he waited for that old priest’s eyes to light up in recognition, see Father, where I am now. But to his disappointment, they did not, and he scolded himself for such pride. As he returned to his standing place, he caught the eye of little Benedicta who watched him intently from behind the gap in her veil. Siegfried diverted his gaze, unsure if looking at this girl constituted a great impropriety. Clothilde arrived next to her sister, her sullen eyes glued on the alter. When everyone sang, the room took their rickety voices and transformed them into a choir.

Frederick invited the steward and his son to the great hall after mass. The leaves had begun to change which marked the beginning of the harvest, and all of Pettau and the surrounding lands prepared for the steward’s yearly visitation. When Siegfried tried to listen in on the conversation between Frederick, Sigismund, and Faroald, Faroald sent the boy a glance so icy, it made him physically shiver. They all hate me, thought the boy, they must truly hate me. He looks at me as though I sully every room I enter. Siegfried couldn't bear the baleful sight of the chamberlain. As for his father, the less time together they spent, the better. Instead the boy took to a corner, shadowed by a great column, and made himself as unintrusive as possible. The best I can do now, he reckoned, is watch them. I really don't know how to be around them. I don't know what these people could possibly want from me.

After mass, some wealthier land-owning vassals, most of them knights in military service to the Pettaus, came with their women and ladies to dance and play music and games, though only some of them were allowed to remain for dinner. Siegfried assumed correctly that this was out of political caution rather than parsimony. Soon the hall filled with people, so much so, that when the Pettau women returned from upstairs in less pious clothing, Siegfried barely noticed. The sounds of a fife and drum reverberated in every direction. From a spot on a sofa Siegfried watched the young men and women dance, hand to hand, walking in circles, hopping in time, gazing at one another. Other ladies gathered in the corners, whispering to themselves while other men huddled around a chessboard to watch Lothar and Arnold test their wits. (Judging by the jeering, Lothar won.)

"Siegfried," said a small voice behind him.

Oh, no, thought Siegfried, who was correct in guessing that the voice belonged to the lord’s youngest sister. Full of dread, he bowed. Why this preoccupation with him? Did she want him beaten before her eyes?

"It was a pleasure to see you at mass today."

The boy merely nodded.

"Do you know how to play chess?"

"No," answered Siegfried, hoping this would deter Benedicta.

"Ah, Frederick should teach you then. Every man should know how to play. The great noble families in France treasure chess greatly. I believe if you ask him, he would be glad to."

"What right do I have to ask him?"

"Yes," said Benedicta, gesturing for Siegfried to sit beside her on the sofa. "It is an interesting question for you. What is and is not your right."

"Everyone will stare at us if we speak, my lady."

"So let them stare. It is my house and my attendant is watching me closely. She glanced sharply to the left, and there indeed stood a stout woman with a coif on her head."

"May I ask why my lady wishes to speak to me?"

Benedicta folded her hands. A little golden ring adorned her middle finger.

"Because you interest me. It is not often that we have a new face join us."

"Novelty wears off…"

"Yes, you are right. But there are other reasons. The way you speak German, with a lisp…I have never heard German sound like that before. Is it true that you can speak Slavic as well as the peasants do? Forgive me if I asked that rudely. I meant no disrespect."

"I am not so far from peasants myself, my lady."

"I heard from Walther that you grew up in the villages. I find that unimaginable. Though I must say, you look German to me. Your nose is a little different, a bit of a hook to it. But my mother told me my father had a Roman nose. Otto had one, too, before he broke it fighting. We have that in common, you and I, I think."

"What? Noses? Yours is far straighter than mine."

"No, not knowing our fathers. Well, I suppose you know yours now. I envy you for it…"

"You really are going to get in trouble for talking to me," murmured Siegfried, not wanting to talk about fathers.

"No, I think that the real fear is that you will be scolded for talking to me. But worry not, I will defend you from any accusations. We Pettau women practice speaking to one another as an art. It would be a waste to never use what we spend so much time refining. And as I said before, you interest me. Half German, half Slav. Our steward’s son. Your mother must have been very beautiful for Sigismund to be unfaithful. What was her name?"

What choice do I have but to answer these mortifying questions? She is a lady and I am her servant. As absurd as it is to be in service to a nine year old. Though I haven’t offered her service yet, wouldn’t it be implied by the service my father offers her mother?

"Siegfried?"

"Hm?"

"Your mother’s name?"

"It was Ajda."

"Was she really a peasant in the fields?"

"Yes and no…She worked as a laundress."

"Oh, naughty Sigismund…"

"Stop," pleaded Siegfried, unable to hide the pain from his face.

"Forgive me" said the girl, with genuine penitence. "What happened to your mother?"

"She drowned in the river," the boy answered quietly.

"Drowned?"

"She lost one of the lady’s veils and when she tried to get it back…"

"So it is our mother’s fault," whispered Benedicta into her hands, "that Siegfried has no mother."

"No, no. It was an accident," Siegfried protested. "You know, we really shouldn’t speak, my lady."

Now the girl seemed to grow impatient. Crossing her arms, she demanded, "What frightens you?"

"Punishment, obviously. But I suppose women don’t receive it…"

"We do. Yet you are a member of our household and thus mine is the right to speak to you. Bastard or not. There is no reason for you to be troubled."

"Pardon me, but I find such thinking childish."

"Yes, pardon you!"

Siegfried tried to apologize, but the offense was already caused. Benedicta left him.

**

"Do you ever see your family anymore?" Asked Walther, after they finished sparring. Walther had beaten Siegfried and thus earned the right to a question.

"How can I see them? Dressed like this?" Siegfried replied indignantly. "They’d spit on me. As is their right."

"You are a strange one, Siegfried. But I suppose I understand. Are you not happy here? With us? Would you really rather be a peasant in the fields?"

"I don’t know what I want to be," Siegfried confessed. "I certainly don't want to have to kill people like your father does, like my father does. The more time I spend up here, the less I understand."

"At least your German’s gotten better," said Walther, no longer interested in the conversation. Siegfried stabbed the courtyard dirt with his sword.

One day, Frederick, of all people, called Siegfried up to the castle. In the great hall Siegfried found him sitting before a chess board. He bowed respectfully, his face taut with nervousness, one that wasn't dispelled when Frederick smiled in his direction.

One day, Frederick, of all people, called Siegfried up to the castle. In the great hall Siegfried found him sitting before a chess board. He bowed respectfully, his face taut with nervousness, one that wasn't dispelled when Frederick smiled in his direction."My sister told me I should teach you chess."

Chess? Really?

"If it pleases my lord," said Siegfried, apprehensively.

"It does. Sit."

Siegfried took the seat in front of him, unsure of where to look. He felt Frederick’s eyes on him and Frederick’s eyes made him feel small.

"You are suspicious of kindness," Frederick observed. "This doesn’t surprise me. People from your parts usually are. A suspicious lot. It’s good for them to be on their toes. It means you’ll be good at chess, too, then. They say it’s a reckoner’s game."

Siegfried understood then that someone had been talking to Frederick about him. However, the lord's aims seemed genuine. The two played chess. For several hours, without distraction, Frederick walked Siegfried through each of the pieces, their rules, their roles, a few select openings the lord liked to use. When the time came to play their first full game, as Frederick suspected, Siegfried proved a fast learner, if easily frustrated. He was bested in less than ten moves, but the next game he survived for fourteen. Upon seeing his error, Siegfried swore under his breath. Frederick chuckled.

"You hate mistakes. Ermenrich told me that about you."

"Oh? And what else did he say?"

"You seem uncomfortable, Siegfried."

He was. "May I ask my lord something?"

"Of course."

"Frankly?"

Frederick opened his palms in a gesture of permission.

"Ever since I came here, I have been received with extraordinary hospitality despite what we all know to be true about me."

"See," the lord laughed, "You are a suspicious! A Slav through and through. Yes, of course. You want to know why. You could use a little political sharpness, Siegfried. Chess will teach you that. As for now, can we agree that frankness begets frankness?"

"Certainly, my lord." It pleased Siegfried that the lord wished to speak to him as an equal.

"You see, your father was extraordinarily valuable to my father and remains valuable to me as well. Without your father, we couldn’t have built our ramparts, our western tower, St. George’s. My God, only the Jews are better reckoners. And while you never saw your father in battle, know that the stories the Slavs tell about him are probably true. He’s killed enough Magyars to populate an Easter feast. Oh, don’t look at me like that, Siegfried. I see no reason why I should censor myself just because you are young. And let me be franker. Faroald has his suspicions about you. He tells me you remain too attached to your family out in the fields and that no amount of finery could persuade you otherwise."

Siegfried's pulse quickened. He thanked God that Frederick was toying with the chess pieces and didn’t see how these words, these accusations, visibly struck him. Perhaps that was part of the lord's strategy, to not look.

Fortunately, Frederick continued nonchalantly, "It's all understandable, you know. Were my kinsmen hurt as greivously as you must feel Sigismund has hurt yours, as untrue as that may be...Your family's is not an easy life, this I know. It is sad that God relegates some of His children to the fields, others to the cloth, others still to the sword, but who are we to question His Qill? And yet here you are, right in the middle. And there is still enough time for you to come around. No lost cause you are. My mother knows all about how you came into this world. She is no stranger to courtly intrigue and rogue affairs between men and women. It would delight you to know that once, a long time ago, she even facilitated a kidnapping – two lords wanting to marry off an unwilling father’s daughters. She sheltered them here, protected their honor, proffered a deal. It is because of her blessing that you find yourself with us. But for the same reasons as Faroald, my father, were he still alive, would not have been so kind. I like to think I am a good mixture of my parents. I may seem young to you, but I’ve seen beyond this tiny, forsaken place, and I can tell you that what happens next in the world's path has consequences for us here. Your people think smally, in terms of surviving winter to winter. But God gave you a bigger mind than that."

Frederick looked up, a slice of light from the window making his clear brown eyes seem, for a moment, amber. "Let me ask you a question, boy."

Tense as a spandrel, Siegfried replied, "Of course, my lord."

"From a span of linen fifteen cubits long and eight wide are cut ten pieces, each four cubits long. How many cubits is each wide?"

What? A reckoning problem?

"Siegfried."

"Can you repeat that, my lord?"

Frederick did so, and in not a moment's time, Siegfried had his answer. It was an easy problem, the kind he could solve when still very young.

"Three," he said.

"Mm-hm." Frederick reset the chess board. "Now, a man hired at a monthly wage of ten pfennigs serves twelve days. What is due him?"

"Four pfennigs," answered Siegfried.

"Explain."

"If you take the twelve days served and cross it by the ten pfennigs, then divide that number by thirty, which is the number of days in the month, the answer is four."

The lord interlaced his fingers. "Perhaps that was still too easy. Now, Siegfried, a ship moves from one place to another at a distance of three hundred miles. It sails daily twenty miles but is driven back five miles daily by the wind. In how many days will it reach this place?"

This problem took Siegfried a little longer to solve. Nervous, he checked his work a few times before answering.

"Nineteen and three-fifths of a day," my lord, he decided.

Frederick whistled with approval. "Remind me how old you are?"

"Eleven on Shrove Tuesday."

"Five and a half years younger than me."

Siegfried frowned. "I thought you were seventeen?"

"No," laughed Frederick. "I am merely tall for my age. So are you, actually. I thought you to be twelve."

The lord’s brotherly attention brought a much self-censored warmth to the boy, who remained secretly proud of the skill he’d demonstrated. A skill the peasants, not his betters, taught him.

"Like I said Siegfried, yours is a bigger mind for the circumstances it was given. Now, I believe Faroald is wrong about you. It’s possible to me that you would betray your father, given what I know about that situation. But," and here Frederick peered up at Siegfried through his thick eyelashes, his mouth drawn tight as a bow, "To betray me?"

Siegfried met the stare. "Betray, my lord? I am only a child."

"Yes, a child. So it is wise of you, one would think, to move beyond childish ideas. I am sure your family out in the fields would love to know the intimacies of those of us on the hill. What we use everything for. Who is and is not in trouble with us. Information, even benign, is powerful. And there are certainly other peasant families that are not as rule-following as yours. Or so Faroald and Sigismund tell me. I never go down there."

"Perhaps you should," suggested Siegfried mildly.

"You are bold." Frederick laughed. "No, there are too many differences between us and them. I would rather have a true ambassador. That would be of immeasurable value to me. It tires your father to have to go down there and negotiate with people who barely speak his language. Violence, I’m sure you know, becomes of misunderstanding. Understanding is very important. For example, I talk to you like you are an adult because you have the intellect of one."

"Thank you, my lord." Siegfried put on a blank expression, pretended to study the situation on the chessboard, but inside his heart raced. It was as though Frederick could read thoughts, sentiments Siegfried himself had not yet completely alighted on.

"I’m sure, too, that even at your young, if precocious age – for we share that in common, our precociousness – you understand the importance, if not the mercy, of negotiation."

The boy wanted to escape this situation. "May I ask directly what my lord wishes of me?"

"Of course. Forgive me, I don’t wish to play any more chess. On the board or off. I will be forthcoming. Five years I want you to stay here at Pettau. Be as you are now. But after Shrove Tuesday, when you turn fifteen, you will go to Graz and serve squire with the Trixens, about whom you learned at dinner, and if not them, then the Wildonies, who are my mother’s kinsmen. I don’t expect any pushback from the archbishop because your father, being our ministerial, is of importance only to us and only we Pettaus know about your existence. You will get a good education there and an understanding of the world. The same education and understanding I myself received. After all, should I become indisposed or merely on a long trip, you, Siegfried, as steward, will be responsible for this town, this castle and by extension the border. Even though he is smiling very bigly, your lord does not jest when he says this. Soon, the time will come when it is my turn to choose my own household. I care little if you are a bastard. Not out of any pity for you, nor in some great display of faith in the concept of merit, but because no one could ever be more useful to the project of this town and this family than someone with your gifts."

"My lord, I am far too young to make such a choice," protested Siegfried, unable to stay silent.

"Yet you are old enough to recognize it as a choice. Playing stupid may work on your father or on Ermenrich, but it does not work on me. The other end of your choice is to end up exactly where you started, back with your uncle, reaping wheat. But worse, because I’m sure there’s no love lost between you and your family now that you have had a taste of the upstairs world."

Frederick extended his hand.

In that moment, Siegfried thought. He thought as quickly as possible, pealing through the contents of his own mind. The day I look into the eyes of those people from atop that horse will be the worst day of my life. And if you don’t, what will happen? You’ll be cast out forever - from Ermenrich, from Walther, from the stables. St. George’s. And then your uncle’s closed door. For years you have avoided the people you loved like a coward. What use are you to them, a body in the fields? And if you don’t become steward, you who knows their plight, you who grew up with them, you who can speak their language, what would happen if someone worse, someone more violent than your father took his place? God gave you this life. God gave you gifts, Siegfried. Who are you, child, to refuse them?

No, it has to be this way. He's looking at me, waiting. He trusts me, even though I don't trust him, and perhaps he knows this. They watched one another think. A long silence transpired before Siegfried finally took Frederick’s hand and shook it.