"Siegfried."

"Yes, marshal."

"When I first met you, you could barely understand me. Or were you just pretending?"

"No," answered Siegfried, "I could barely understand."

"Now you seem to understand everything I say, which, if true, is remarkable. You have a gift for words, it seems."

"Thank you," said Siegfried, "but it is only out of necessity. And I worked on my words after going home. I wandered around the houses of my German neighbors. One family a hide away from me doesn’t have any sons and so I help their daughters carry water from the river. Sometimes they let me eat dinner with them in exchange and I practice that way."

"And what about your own family?"

Siegfried looked away, even though it was disrespectful. "May I speak truthfully, marshal?

"You may."

"They don’t care whether I come or go. I don't work as much as the others because I'm up here, and they see me as an extra mouth now. All my life others in the village have accused me of thinking myself higher than them, and now my father has given them a reason to. And now that my mother is gone...You know, even when my mother was alive, we were the two of us alone within her own family because of me." Siegfried didn't know why he told the marshal the truth. He probably would have told the truth to the first person to ask it of him.

“We were the two of us?”

"Ah, that," the boy smiled bashfully. "I can’t quite get the hang of that. You see, marshal, in my language when there are only two things together, we have a special way of talking about them. Two is a number all its own, different from all others. A whole word or sentence changes when there are only two things. In German there is no such twoness. Only one and many."

"You should spend more time up at the castle," said Ermenrich, "so you can learn better than peasant German."

"But I am a peasant," replied Siegfried. "And besides, I’m not allowed."

"Yes, this business with your father’s wife. Women are like that. Vain, easily injured, wrathful as a wasp. Well, come to the stables, then. Tend to the horses. We’ll give you a place to sleep in the hayloft."

"With all respect, marshal," said Siegfried, stopping; "I don’t like when people feel sorry for me. I prefer to be where I came from and unlike many people, I know exactly what I am."

The marshal laughed. "That’s pride talking, Siegfried, and you are in no position to be prideful. You know, when your father named you that, I tried to warn him it would come with a price."

Siegfried grimaced inwardly. "Yes, this name of mine. Where does it come from?"

"Come to the stables, boy, and I’ll tell you."

When Siegfried came to the stables the following day, he felt sick with a sense of betrayal. Regardless of whether the people at home loved or wanted anything to do with him, with them was where he belonged. The allure of the better, higher world, he believed, was a trap. Sword fighting aside, the more time he spent on that hill, the more fraught things became back home, the more he loathed the very idea of the joining the people that violated and killed, if indirectly, his mother; the idea of those people inviting him in. He trusted no one there, not his father, who remained absent - though not as as absent as Siegfried thought - traveling around the unceasing Pettau estate or away on military drills near the border, nor the marshal, whose sudden generosity Siegfried found unconvincing, if secretly welcome and desperately needed. Yet the boy’s curiosity proved powerful, and even more powerful than his curiosity was his desire to be accepted somewhere, anywhere. Other boys were a lost cause, but maybe, if he got along here with the marshal and these military men, he could somehow, down the line, use such connections and knowledge to help his own family. Protect them from harm. This sentiment he kept silent to everyone as though it were the world’s richest secret. So rich, as soon as he alighted onto it, he hid from it, as though not ready to think it.

Ermenrich introduced Siegfried to the men of the garrison and the castle guards, who, outside of their armor were the same sweaty drunks Siegfried had long been familiar with. Around a wobbly wooden table, they came and went, drank and ate voraciously, and Siegfried, for whom chicken was a feastday delicacy, had to physically restrain himself from devouring everything in sight. Walther arrived not soon after, wanting to be around his father. The boy, whose hair still retained its childhood whiteness, peered at Siegfried warily, but said nothing.

"A Slav who can speak German like a little lord," joked Audowin, one of the guards, a man so large he made the stool he sat upon appear childlike. "Now I’ve seen everything."

"Less like a lord, more like a scoundrel," said Siegfried, and the men cheered.

"The lisp on that boy! He sounds like a serpent. My god, Ermenrich. And you say he’s Sigismund’s son?"

"Who else would name his own bastard Siegfried?"

For the first time in a while, the word bastard rankled the boy.

"The stories are in some way wasted on all of us," Audowin said into his cup.

"What stories?" Asked Siegfried.

"Ignorant as a baby, he is. You people down there know nothing about the late Lord Frederick or his delusional wife. Or of Salzburg..."

"Delusional?"

"Crazy, he means," chimed in Walther, smiling. Siegfried glared at him.

"Why should we have to know anything about them? They’re just the people who take from us."

"Watch your mouth," muttered Ermenrich.

"He’s just learned how to speak and is already speaking his mind," said Audowin. "Well he’ll have to shovel shit for it now."

"I shovel shit anyway."

Everyone laughed. Yes, laugh, thought the boy. "But what about these stories," he insisted, irritated.

"God bless our late Lord Frederick," began another man, a sharp-nosed fellow called Gislin, "but he was given the mind of a soldier and not that of a courtier. His wife Benedicta, however, is from a noble family up there in Austria, and she always passed down these stories about the old Gothic kings. And then, when we all went together with the Archbishop to Salzburg, we heard even more of them. A bunch of fantastical nonsense for aspirational princes and bitter ministerials if you ask me."

"Not me," said Audowin. "I love that stuff. Dwarves smithing rings, dragons, all that. Dietrich of Bern and his magic sword."

"Yes, and he never loses, does he? That’s why I find it silly."

"But the story of Siegfried is not silly."

"No, Audowin, not at all. God, look at that boy, he’s about to leap out of his seat if we don’t tell him. Marshal?"

"God knows I’m terrible at it."

"Fine, I’ll do it," said Audowin, who began:

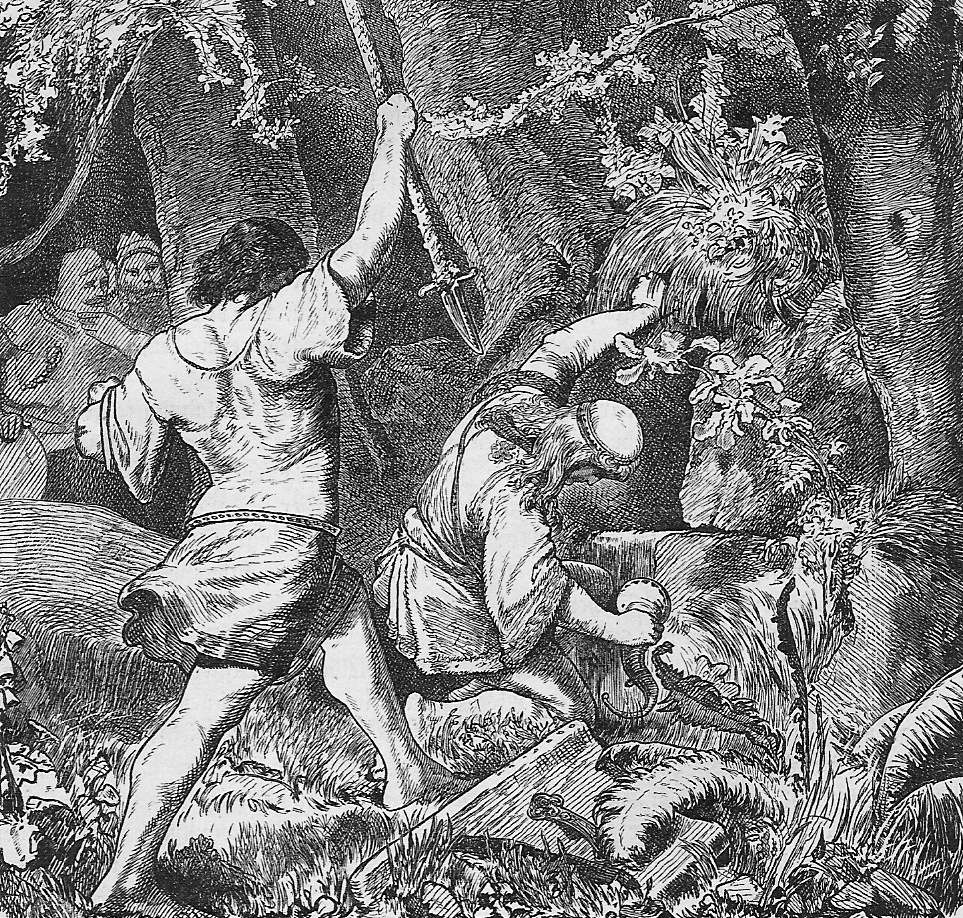

"Once in Old Germany by the shores of the Rhine, there was a wandering warrior raised by a dwarf."*

"No, Audowin. Not that version. Do the other one, where he's raised by normal, noble people."

"I like that version, and I’m telling the story. Anyway, this warrior was named Siegfried. As a boy, he was strong as could be and very rebellious. He caused his dwarf father so much agony growing up that the dwarf sent Siegfried to go slay a dragon, who was in fact the dwarf’s brother, who could by magic turn into a dragon. The dwarf did this hoping that the boy would die, as no one had ever been able to slay this dragon before. They say the dragon was as big as a house and with teeth that were coated in poison, so that if the dragon bit you, you would die anyway.

But Siegfried was no ordinary young man, and so he slayed the dragon with ease, some say even without fear – and then, naked as the day he was born, because the dwarf had given him no clothes, he coated himself in the dragon’s blood, which made his skin hard as armor, save for a single place between his shoulders, as a leaf had gotten in the way."

"Don’t forget he could understand the songs of birds," added Gislin.

"In one version…Anyway, slaying the dragon came with a great fortune, a cloak that made Siegfried invisible when he wore it, and a sword called Balmung, which was made of unbreakable steel, forged by dwarfs in their dark caves. And so Siegfried became very rich, and a famous warrior, known everywhere, respected by all. You know, it was said, and we still say it now, that no one was ever stronger, more noble, or a greater friend. Yes, smile, boy, but don’t get too prideful. Anyway, in his wandering travels, he met a princess Kreimhild, who was very beautiful, and in order to marry her, he made friends with three Burgundian kings. Gunther, Gurnot, and Giselher, though you only really need to know about Gunther, Kreimhild's brother. I don’t remember what the other two did. Why look at me like that, Gislin? I'm sorry I'm not the best regaler of all of this but in my defense, it's a lot to remember. I don't know how poets do it and we didn't even learn it from them.

Regardless, Gunther had a woman of his own he wished to wed, Brünhild, the warrior queen of Iceland who was stronger than all men. Yes, a woman who fights with the strength of five men. Gunther himself was not strong enough to brige the ring of fire required to woo her, and so he had to ask Siegfried to help him, which Siegfried did, in exchange for the hand of Kreimhild. As part of the scheme, Gunther claimed that Siegfried was his vassal, and thus was allowed to in the task of braving the fire. Once the two defeated her, Brünhild and Gunther were wed, and so were Siegfried and his beloved Kreimhild.

But Brünhild saw Gunther for what he was, which was a weak man, and refused to allow him to bed her. To his humiliation, she tied him up by his belt from the rafters, and when Gunther tried again, she did the same thing. Thus, Gunther enlisted Siegfried’s help once more. This next time, Siegfried, wearing his cloak of invisibility, overpowered Brünhild and held her down so that Gunther could finally have her, and with that all of Brünhild’s unnatural strength was taken away and she became then no different than any other lady. As a reward for his conquest, Siegfried took Brünhild’s belt and ring and showed them gleefully to Kreimhild." At this, the men all howled and jeered.

"But why would Siegfried do this to Brünhild?" Asked the boy of the same name, who thought, of course, of his own mother and the steward and the storeroom. A woman pinned down, a woman robbed of virtue. He searched all these faces for any indication of apprehension. To be strong was such a crime that it warranted a crime in return, and that crime didn't even look like a crime to these people, but a joke. Siegfried wasn't raised in the same way as these men, and to him, a strong woman was a relief to the rest of the family the whole year long. Maybe not the most beautiful, those rounded shoulders, big hands. But work was work. And to every woman, no matter her appearance, a husband, children, family, all out of necessity.

Audowin looked at the boy askance. "I told you, because Siegfried was the greatest friend anyone ever knew. He pledged himself to Gunther, to help him, made an oath of loyalty, and this was part of following that oath. Besides, a woman shouldn't be like a man. Nature was righted that night. A little pain before pleasure...Much of life is like that, boy. Anyway, so it went. One day, the two queens both arrived for Easter Mass at the cathedral in - was it Worms, Gislin?"

"Why the hell would I remember? Call it Worms."

"Fine, Worms, and they disagreed about who was more noble and therefore entitled to enter first. You must remember that Brünhild thought Siegfried was a mere vassal, and therefore Kremhild was only a vassal’s wife. This offended Kriemhild who, with the belt and ring as proof, claimed that it was Siegfried, not Gunther, took Brünhild’s virginity. It doesn’t matter that Siegfried denied this over and over again, Brünhild was so angry, she vowed revenge. Out of shame and indignation, Brünhild decided to murder Siegfried and made Gunther come along for the ride."

But how do they know how to kill Siegfried?" Asked the boy. "Since he has all that armored skin?"

"Brünhild ran to Gunther’s half-brother Hagen, who was very clever. He went to Kriemhild with remorse, and tricked her into telling him about the weak spot where the dragon’s blood didn’t touch. And so Gunther invited his friend Siegfried on a hunt with him and Hagen, and when Siegfried stopped to take a drink at a stream, Hagen killed him, driving a spear between his shoulders, right where the weak part of his skin was. As a trophy, Brünhild had Siegfried thrown outside the doors to Kreimhild’s bedroom, and there she and her whole kingdom mourned him greatly."

"And that’s how it ends?"

"Well, Kreimhild waged war on Brünhild and many people died, including Gunther. The story goes on from there, but I forget the rest. I think this was how Dietrich of Bern was given his wife, Herrad. Because she was a friend of Kreimhild, whom he helped in battle."

"No, moron, you’re thinking of the wife of Attila."

"I heard it was Etzel, not Attila," said Ermenrich.

Siegfried, almost on the brink of tears, asked, "Why would my father name me after such a terrible story?"

"I’m not very good at telling it," admitted Audowin. "If I were better at telling it, you’d all be sobbing."

"Don’t be morose, child," scolded Ermenrich. "Who doesn’t want to be named after the man everyone agreed was the smartest, strongest, most loyal among them? Who slayed dragons and won maidens? Are you mad? The real lesson here, of course, is to be wary always of women. You never know what they’ll do."

And at this, everyone except the boy laughed.

Soon, Siegfried spent all his time at the stable, where he worked as a stable boy, something he preferred infinitely to both the constant trip between town to field, and to his previous labor. Horses were a rich person's animal - there were horse people and oxen people - and the horses in the big stable were glossy-coated and tall, muscular and sometimes poor-tempered, at least when they were young. There were some near misses walking behind them, but soon the horses all got used to Siegfried. He groomed them, mucked their shit, walked them when they got restless, fed them. He loved how they smelled, like hay and hair. He knew them all by name. The lady's black horse, a mare, named, unsurprisingly, Brünhild; Ermenrich's charger, Dietrich, dappled with the long hair around his hooves; Siegfried's father's dark bay horse, Aistulf, and the horses that came in and out, from the guard, from the border towers, the horses who lived at home with their owners, all taken to Siegfried for maintenance. Some of the only times he saw his father, was when Sigismund came to get his horse. And each time, they would have the same terse conversation, in which Sigismund asked Siegfried how he was, and Siegfried always said very little in response because he knew, he could tell, it hurt his father. In the stable, where a handful of men remained garrisoned on an on and off basis, depending on how bad the Hungarian threat became, it was always warm and full of the companionship of men at arms, their stories, their hearty diets, their refreshing vulgarities. They cycled through like the seasons, gave Siegfried ale and mead, which he hated because it made him sick. It was through them he learned about the Hungarians and the battles, which sounded harrowing. Standoffs in archery towers, ambushes on open roads, rather dishonerable skirmishes. And the clothes the Magyars wore, all bright and colorful, mustaches instead of beards, closer to Turks than Christendom...

But most of all, staying at the stables gave Siegfried the permission he needed to no longer feel like a burden to his family in the fields. He said it to himself all the time, whenever he felt lonely or homesick: One less mouth to feed. I wasn't helping much anyway. And with my mother gone...And yet, at the same time, he missed his aunt and uncle and carried the persistent guilt of abandonment. Fulfilling his prophecy. But, he repeated with the insistency of a prayer, his mother said, you were not meant for this life, Siegfried. Back and forth he went, never with a certain answer. To a little boy, his seemed an impossible situation. Often, he spent nights in tears, deliberating, not knowing what to do. He kept this burden to himself. No one here would understand. Why would he ever want to go back into a life of poverty and toil?

At the beginning of his stable residency, he went down into the fields on the weekends to help his uncle. But when his uncle began refusing Siegfried’s help, the boy didn’t know what to do.

"Are you going to start carrying a sword now too?" Asked Jarilo, weaving twigs to patch up the holes in the house.

"If I’m asked to," said Siegfried.

"Why bother with us, then? There’s nothing more insulting than the pity of a child."

"But I don’t pity anyone," the boy protested, "You are my cousin, and that is my uncle."

"And your father comes twice a year down the same hill you walked up every day."

"I don’t like that he’s my father."

"Yet you wear the nicer clothes given to you."

"By the men in the garrison! I am not allowed to see my father."

"And yet in the stable you stay."

"None of you would give me clothes when mine were moth-eaten and worn to shreds."

"Why should we, now that you go up there?"

"What do you want me to do?"

"Oh, now he cries? What right do you have to tears?"

And so Siegfried, out of shame and rejection, and to protect his heart even further, avoided his family. Dutifully, he brushed the horses at dawn, mucked the stalls, polished the saddles, which were embellished with silver. In exchange, Ermenrich gave him instruction in horsemanship, at which, unlike sword drills, he immediately excelled. He found his balance easily and knew horses well, had no reason to be skittish. It was a dream of his, riding a horse, instead of sitting on the back of the oxen as an even littler child, being led around by his mother to help spread the manure. No, Siegfried loved the feeling of a horse beneath him, the sensation of moving in great strides across the earth, the potential for efficiency and daring, the duality of his hair and the horse's mane in the same wind. A horse gave him power he’d never known before, a channel for a kind of innermost energy. Like all children, Siegfried felt that horses loved him. The way they snickered and whinnied, the way they nuzzled their noses in his palm, their gentle eyes. Sometimes in lieu of the hayloft, he slept in the stall with the broodmare, curled up against her big, heaving chest.

His learning elsewhere continued to prove a little slower. The transition away from a wooden sword to a dull, metal practice one made him sick with dread. When faced with the heft and the threat of even a blunt edge, he could stomach blocking and parrying, but became unsteady and precious when attacking first. On this, Ermenrich often worked with him after the day was done, wearing the boy down with exercises until he grew so frustrated whatever mental blockage kept him from throwing his weight around eventually disappeared.

"You’re more embarrassed of making mistakes than you are afraid of harm," the marshal observed. "The answer to that is to simply not make mistakes."

Something about those words unlocked a solution. Instead of feeling beholden to the sword and where it was going, Siegfried began to rely on that same skill of reckoning, of counting, the one thing that calmed him. If he could translate the motion and rhythm of swordsmanship into numbers, then he would have mastery over his mistakes simply because they were numerical mistakes. Counting kept him calm, steadied him. The other sword was not a threat. Only a number. One, parry two, dodge, parry, step back, counter, four, strike, five...

Meanwhile, Siegfried and Walther spent more and more time together. They became, if not friends, then stablemates. Walther’s was a genial, even-keeled disposition. He seemed friendly with everyone, in part because he was the marshal’s son and others respected him automatically. He didn’t have to wrestle the respect out of them. But when he once stood up on behalf of Siegfried, who was being pushed around by the other boys, Siegfried scolded him harshly. Help me on my own terms. Not on yours. This display of honor impressed the other boy, who decided the best course of action was to lend Siegfried his presence as much as possible. As long as they were together, no one would bother them. Siegfried understood this, and was grateful, if still wary. This was the final of his problems up on the hill, aside from that of his father. Once Walther spent time with Siegfried, the other boys gradually accepted him also. Bullying him got tiresome, especially since it affected him so little, since he held his head so high. No one was friendly, but settled instead for the absence of cruelty. For the first time since his mother died, life began to slowly relax for Siegfried, attained a rhythm, a new one. It was an easier life than Siegfried had ever experienced. He slept on hay instead of the ground. He slept in a warm, clean stable. He dressed in ordinary clothes, those of a townsman. Stockings without holes, new leather shoes, a linen shirt with a brown wool surcoat, cinched neatly with a belt. Soon, a sword on one hip and a dagger on the other. When he got lonely he told himself his uncle's stories. Often, he imagined his mother and spoke to her, as though she were there, sometimes for hours. When he slept, he so often dreamed of his past. Of the linden tree, of his family, of the pigs and chickens, the oxen, the rhythm of life, the harvest, the reckoning, the cold, dark nights, the sound of winter. When he awoke, he listed all the things he wanted to remember, monomaniacally, terrified of forgetting anything, especially his mother's voice which was fading ever-more from his memory. Then he would dress himself, and walk up to the courtyard, the faces around there more and more familiar, reminders that time moved only forward and with it, life. Thus Siegfried became a child raised indirectly, in piecemeal, responsible for himself. Transient as a bird, which was what his uncle said of his father.

**

When it came time for the harvest to be collected, the steward’s son hid in the hayloft for two days and wept.

*The version of this story is a compilation fashioned from the Siegfried stories from the Nibelungenlied and the Nordic version of Dietrich of Bern. These are old stories that would have been widely known at the time, despite the lack of written record.