The day the steward sent for Ajda, she was at home with her son, who suffered from a low fever. The metallic timbre of the knock at the door alone told her who could possibly be calling at such a time. Stricken with fear, she whispered to a barely-awake Siegfried: be very quiet. For a long moment, the two of them sat perfectly still, hoping that the man would leave.

"I know you're in there," a voice said. A voice that wasn't Sigismund himself. "You can open the door or I can beat it down."

Thinking quickly, Ajda threw a blanket over her son, who understood what was being asked of him. She opened the door just a crack to see one of the steward's men, who stuck in his hand and wrested it fully open.

"The steward wants to see you. Up at the castle. He says: 'Where you usually meet.'"

"Only me?" she asked cautiously.

"As far as I know."

Ajda glanced back into the house with worry.

"Tell him I can't see him now. My son is sick."

"So bring the boy," said the man, pawing at his dagger. "It isn't a choice."

And so Ajda, for the first time in many years, walked across the field, across the Roman bridge, through the town and up the castle hill, Siegfried in tow. Despite his fever, the opportunity to see the town and the castle up close helped him keep his mother's brisk pace, if a little deliriously. He tried to get his mother to stop rushing so he could make the many observations children love to do when in new situations, but she pushed on regardless. He wondered what was happening and why his mother seemed so upset, and in this much of a hurry. Without issue - after all, the laundress Ajda was no stranger - the pair passed through the gate. Siegfried found himself dazzled by the presence of a fully-armored guard wearing that same, strange, spiky symbol on his surcoat. The armed men who ran through the village on horseback wore it too. For the first time he saw the colonnades of the inner castle courtyard and strained to check if anyone was walking around. When only a raven made itself visible, Siegfried pouted with disappointment. Mother and child entered through an inconspicuous door, where Siegfried found himself in the biggest kitchen he'd ever seen in his life. A massive hearth, shelves with all manners of vessels and bowls. Pots, tools for tending the fire, a ceiling that swallowed him up...

"Wait here," she told him. "Don't touch anything. If someone approaches you, use your best German. I’ll be back soon."

At first Siegfried waited, wiping the sweat from his forehead. Was that a big smithy he'd seen in the town? And all those houses! Every horse walking by was tall and beautiful. Which herbs were drying on the wall? What could they possibly cook in so big a pot? And the hearth had a hood on it that kept the smoke from getting everywhere. They must smoke their meat differently than we do. Or have a separate place to do it. He wished he got a better look at the castle. Why was no one out in the courtyard? Maybe they were all inside doing something. Imagine seeing the lady! Or her children! What could noble children possibly be like? He wondered. However, beholden to his curiosity, Siegfried became restless. What was his mother doing? And why was it taking so long? Worry clouded him. He didn't like being alone in the kitchen, where someone could stumble upon him. Then what would happen? They'd probably assume he was a petty thief...

Nervously, he opened the door his mother had entered and discovered a dimly lit hallway. At the other end, a sliver of light. That must be where she is! He heard voices. His mother's and one he didn't recognized. He froze. At first he thought they were arguing, but he wasn't sure. He didn't speak German as well as his mother, who spoke it better than everyone else in the family. He wanted to see who the other person was. He knew from the voice that it was a man. With trepidation, Siegfried crouched down, pressed his fingers against the door so that it would open just a little further, just enough to see. It was a storeroom, full of barrels of wine, lit only by a couple of small, high-up windows with grates over them to keep robbers out. There he found his mother, yes, but also the steward, whom people had pointed out to him while working in the fields. The steward, Žiga, who everyone feared and nobody liked. What did he want with his mother?

He squinted his eyes, trying to see closer. Now, they were speaking in low voices, very close to one another. His mother sounded tearful. He couldn't see the steward's face, only the back of him. The steward, touching her hair. Don't touch her! But his mother stayed perfectly still. Looking at him with shining eyes. Then the steward covered her mouth with his, then his mother began crying, but didn't fight back. Then he pressed her against the wall and…The boy's eyes widened. In absolute terror, he watched the scene unfolding, wanting to intervene, wanting to be brave – that’s my mother, that’s my mother – yet feeling completely trapped, hopelessly trapped. Rural life had exposed him to such things young. He knew exactly what was happening and why it was wrong. Why didn't his mother do anything to resist, not even yell? Why did the steward want to do this to her? Stop, he begged inwardly, tears running down his face. Please.

The steward paused, panting. He looked around. The boy sucked in a breath. Was it possible the steward heard him? Siegfried didn't know what to do. He didn't know what to do at all, whether to stay there or scream and get them to stop, or whether the steward would harm him if he got caught, and what was that sound? Footsteps? Siegfried's body decided for him and took off running. He ran and ran and ran, barely watching where he was going, trying to remember how he'd even gotten up to the castle. Once he saw a glimpse of the river through a gap in between two houses, he tore off in that direction until he found the spot where he knew his mother washed the clothes, right by the bridge. And yet he didn't want the laundresses to see him. He didn't want anyone to see him. Where was he? Where could he go? At once, he saw a large willow tree, its fronds so long they touched the ground and there he ran to seek shelter, so breathless from running, terror, and fever that he began to heave. And once he caught his breath, he pressed his face into the dark soil and screamed. He screamed like the pigs did when his uncle ran after them, the pigs surely knowing what would happen to them should they be caught. Siegfried felt like that too, a stupid animal, incomprehensibly afraid. Not only afraid, but cowardly. He had abandoned his mother!

Most of all, he was angry. He knew his place in the world. He was no stranger to it. He heard the way his aunt and uncle and kinsmen and women talked about things as they were, about the dues and the collection, about starvation and brutality. Stories about the tax one paid right after someone died, about the punishment that came to families who couldn't pay their dues - being beaten; having their oxen taken, putting them at risk of starvation; having to give the steward twice as much next year even though the fields could only grow what God had allotted them and no more. And now, even though his family had always been timely with the dues and the rent, the steward was punishing them by doing the worst thing a man could do to his mother. Who ever heard of such a punishment? Who ever heard of such evil? He takes! thought Siegfried; he takes and takes and takes! I’ll kill him. I’ll kill him with my own hands. I'll take the sword right out of his scabbard and slice his head open. And then when he's dead I'll cut his prick off and feed it to the pigs. I’ll die if I have to, but I’ll kill him. I will. But, more than anything, Siegfried wept because now it all made sense: the way he’d been treated, his mother’s aversion to his questions, everything, everything – he had no father! Of course he had a father. Now that he knew who that father was, he wished he had never been born. He begged God to tell him that this was all just a feverish nightmare, and if it wasn't, to take this knowledge away from him, to clear the very day from his memory. He wished even more that he didn’t know exactly what it was he saw. And oh, God, his mother? Was she hurt? She was crying…pinned like an animal by the man who steals everything.

Still crying under the willow tree was where his panic-stricken mother found Siegfried hours later. If she weren't so relieved to see him, she would have raised her own hand to him. But the sight of him crying softened her anger. She wiped the dirt from his face, told him how worried she was. Held him in her arms until her pulse finally began to slow down.

When she asked him what was wrong, Siegfried murmured into her shoulder, "Now I know why they call me Žiga."

And there, now in tears herself, Ajda told her son as much as he needed to know.

"I’ll kill him," Siegfried said again. "I’ll kill him."

"No," chastised his mother. She sighed. She smoothed his hair, ran her palms down to his shoulders, looked her son directly in the eye. And, looking at him like that, she spoke to him for a long time.

"I know this is all very hard on you," she told him. "But I'm begging you to hear what I have to say. This whole time, when all those people were cruel to you, they knew, not the truth, but part of it. Forgive me for not telling you earlier, really, forgive me. You see, for years your father left me alone, you alone, and I thought he would keep doing so. I thought you would grow up not having to know all about this. The truth changes so little, Siegfried. I love you as I have always loved you. Just because you came into the world like this does not mean for a moment that I love you any less. As hard as this may be for you to learn, you must understand. Your father told me right before you were born that he would provide for you when the time comes. He told me that no son of his would ever grow up to kill pigs and reap wheat. This is the only good thing to come of him being your father, that you will grow up and not have to toil, that you will suffer less than I have suffered. Listen to me. You were not meant for this hard life, Siegfried. It is God’s will. God made you this way. God gave you these circumstances. God gave you gifts. Who are you, child, to refuse them? Who?"

Bad things, it was often said by the people in those days, often happened in pairs.

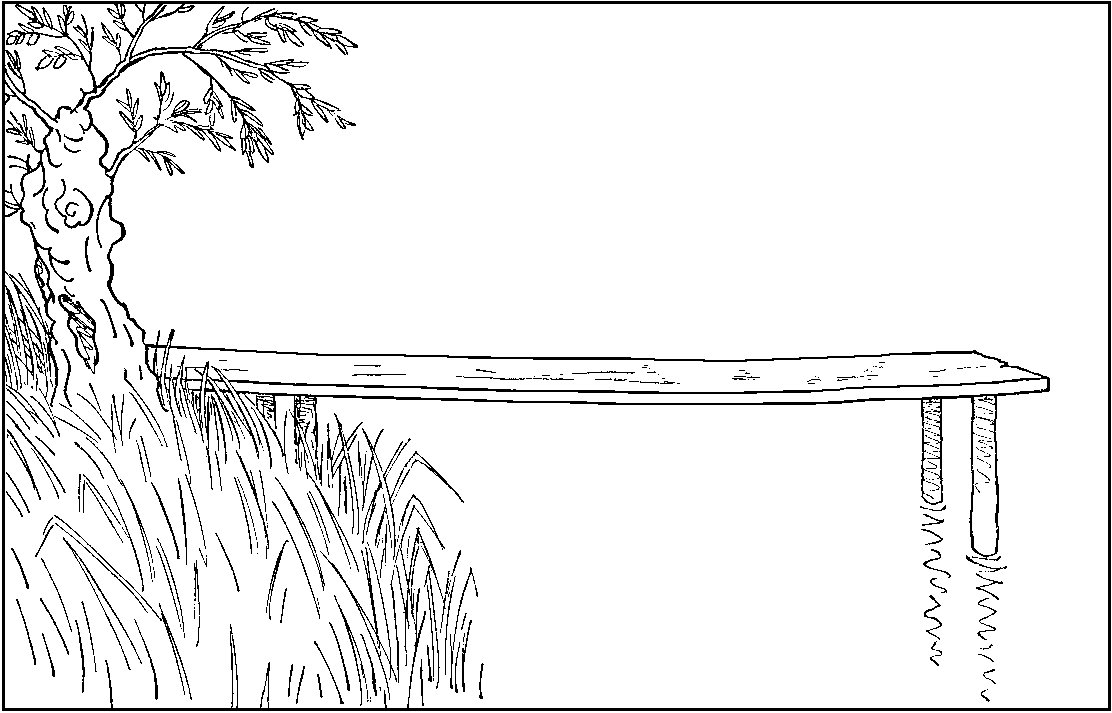

One day, a few months after the incident at the castle, Ajda was washing linens in the river. To her dismay, one of the lady’s veils escaped her grasp and began to float away.

"Go in," the head laundress told Ajda.

"I can’t swim," she protested. "And the river is moving too fast."

"You’ll get a beating if you don’t."

I should at least make a show of trying, Ajda thought. Just wade in a little bit. Look, I think that's it over there - caught on a branch.

Ajda then stepped into the river and never again came out.

By the time they found her body, a mile or so downstream, it was swollen with water, the eyes wide open. The family couldn't afford a coffin on such short notice, and so they wrapped Ajda in cloth and buried her under the linden tree next to the house. Inconsolable, Siegfried sat beside the shallow grave and wept ceaselessly. No one could help him, and he refused everyone that tried. For three days, neither threat nor persuasion could bring him inside. Without even a blanket he slept and awoke there, and each time he awoke he remembered what had happened and wished again for endless sleep. Maybe when I wake up next time, he prayed, all of this will have been only a dream. A nightmare. It couldn't be true, he told himself over and over again. It couldn't be true that his mother was gone. It couldn't be true that he now lived in a world where nobody loved him. And yet it was true. With each passing day, it only became more true. Perhaps, on the day the steward finally came to collect his son, it was the most true it had ever been.