In the house everyone kept busy and there was always something for Siegfried to do. By the age of four, childhood idleness was no more, and he began to understand that what made him what he was - what made him part of his family and the people around him - was work. It didn't matter if they were young or old, men or women, weak or strong. The potential for starvation and indebtedness affected everyone equally; worry ruled the day rather than reward. Like all children, Siegfried enjoyed helping and clamored towards any opportunity to be a part of the lives of adults. People were nicer to him when he helped them. He quickly understood that work possessed a redemptive power. To be tired was to be good.

The year moved forward not in time but in tasks, seasons and their responsibilities. Epiphany was the time of repairing, mending what the prior year had worn. The women darned stockings and patched clothing and blankets. When the snow began to wane, Bodin, Siegfried, and his cousin Jarilo, then a teenager, bundled up the best they could and ventured out to the edge of the woods to collect sticks. Bodin and Jarilo used knives to pare twigs from branches, while Siegfried picked them up from the ground if sufficiently dry. They bound the twigs with twine and carried them over their shoulders or under their armpits and stayed out until they could either carry no more, or when their hands and feet began to turn numb. Everything was so quiet, the colder Siegfried became, the more he believed that winter had its own sound. A hollow sound that mingled with the wind passing over his ears, a tone lower than any whistle. When they returned, they brought the sticks inside to keep them dry. The next day, Bodin shoveled ox and pig shit while Jarilo and Ajda sat by the fire, weaving the twigs. When they were finished, Bodin then used the shit as spackle to mend the holes in the walls of the house. Patching the holes was best done in January, Bodin explained, because the air was so cold and so dry, the shit hardened faster. This was the only utility of the cold.

February brought back nature from where she was hiding, and with it Siegfried's birthday, which was only ever remembered because it was Shrove Tuesday. Even though Shrove Tuesday fell on a different day every year, it was still Siegfried's birthday each time. Despite having all but exhausted their resources, people in those parts still found ways to celebrate. Because they had nothing to give to Siegfried, every year his uncle told him a new story, which delighted the boy to no end. Indeed, no matter how miserable winter and the coming labor could be, the boy and his family were often quite happy. Special meals after the harvest, on Easter and Christmas. The first taste of pork every winter. Music, play and laughter. A new garment every once in a while. Often, people came together and danced, if only to keep warm. Kinsmen got married and babies were christened.

But Shrovetide was the only time Siegfried ever saw people drunk beyond their senses. Men he knew became different men. Women tore off their headscarves and became different women. People gathered around bonfires well into the wee morning. On Shrove Tuesday itself, the unmarried men in the villages donned their sheepskins and bells, their horns and sticks embellished with hedgehog skin, and dressed as Kurent, the old god of wine.* Siegfried hated Kurent. He found that long leather snout, the red tongue emerging from a gaggle of sheep's teeth to be wrought from the stuff of nightmares. Of all the possible ways for a god to look, he wondered how his ancestors settled on that one. And though everyone laughed and laughed, Kurenti chased all the unmarried women and picked them up, grabbed them all over, carried them away from their families and frightened them to death. Siegfried's own mother, just as she did whenever the steward came to call, preferred to hide in the house. And whenever his mother stayed in the house, despite what was happening outside, the boy preferred to stay with her.

The old stories about Kurent, however, Siegfried enjoyed because Kurent was a trickster. It was said that when mankind's greed and lecherousness made God flood the earth, the last Slav was standing atop a tall hill, and as the waters rose, he kept seeking higher and higher ground, until, on a rocky crag, only a single grapevine remained. And so, in desperation, the last Slav called for Kurent, the god of wine, to save him. Kurent took the vine and ripped it out of the earth, carrying the last Slav high into the clouds with him, where the man was able to survive on grapes and wine alone until the flood subsided. In another story, when Death came for Kurent, Kurent offered Death a golden apple. He rolled the apple across the floor, and when Death followed it into a jar, Kurent trapped him in there and it was said that no one died for seven years.*

After Shrovetide, Bodin saddled the oxen Perun and Svarog to the plow shared between several families. Perun, named after the god of storms who lived up in the sky on an impossibly tall mountain, and Svarog, the god of the sun. Rain and sun made the harvest together and Bodin stubbornly believed that naming the oxen made them less fickle and onery. When the oxen dragged the plow along the earth, huge clods sprung up and what was once a dull brown became black and rich. The smell of shit and earth meant that the year would renew itself, that hunger would end and trees would flower. Lent began and people came out of their houses. Men took last year's seeds and expertly sowed them. First vegetables - peas, beans, onions - in the garden right when the ground thawed; later barley in case the wheat planted in October failed or was damaged by storms. Some preferred to work with their shoes off rather than to ruin them with mud, and to a young boy, after the smell of shit died down, there was something satisfying about smushing the earth between one's toes. Once, when he was four, Siegfried ran out of the house naked and rolled around in the mud like a pig, an event people regaled to him every spring much to his great embarrassment.

Like all children, from a very young age he was put to work in the fields. His first jobs consisted of pulling weeds and scaring birds. The first, he loathed, the latter, he loved. The two active fields were not small, and even though everyone in the household - Ajda, Siegfried, Bodin, Marija, Jarilo - and Bodin's grown children who all had formed new but landless households of their own - helped with the weeding, it still took from sunup to sundown on any given day. The act of bending and rising, bending and rising so tired Siegfried that he devised a plan to save energy by crawling on his hands and knees. But when Bodin's eldest son Krešo discovered the boy's cleverness, he barely escaped a beating for having kicked up so much dirt, potentially disturbing the seeds.

Scaring birds, however, was fun. Barefooted, Siegfried ran through the fields the second he alighted on any movement. Singing and shouting, he carried an old sheepskin drum which he rapped with the palm of his hand. "Go after the ravens first," advised his uncle. "You know the story of the raven? Well, it was once said that the raven used to be pretty as a finch and have the most beautiful of all birdsongs, so beautiful that men, women, and children would stop to listen to it for as long as they could. One Easter Sunday, despite it being such a sad day, the raven, to whom God had given such beauty, became arrogant and sat in his tree singing and singing. The song was so beautiful that the people on their way to church missed Mass altogether. God was furious, and swore to take his revenge on the raven. He stripped it of its beauty and made it the ugliest of all the birds with the ugliest of all songs. And to pay back the people for having ignored Mass, instead of singing for them the raven was given a large appetite and was then sent to ravage their crops. Ever since then, our poor lot have had to deal with ravens."*

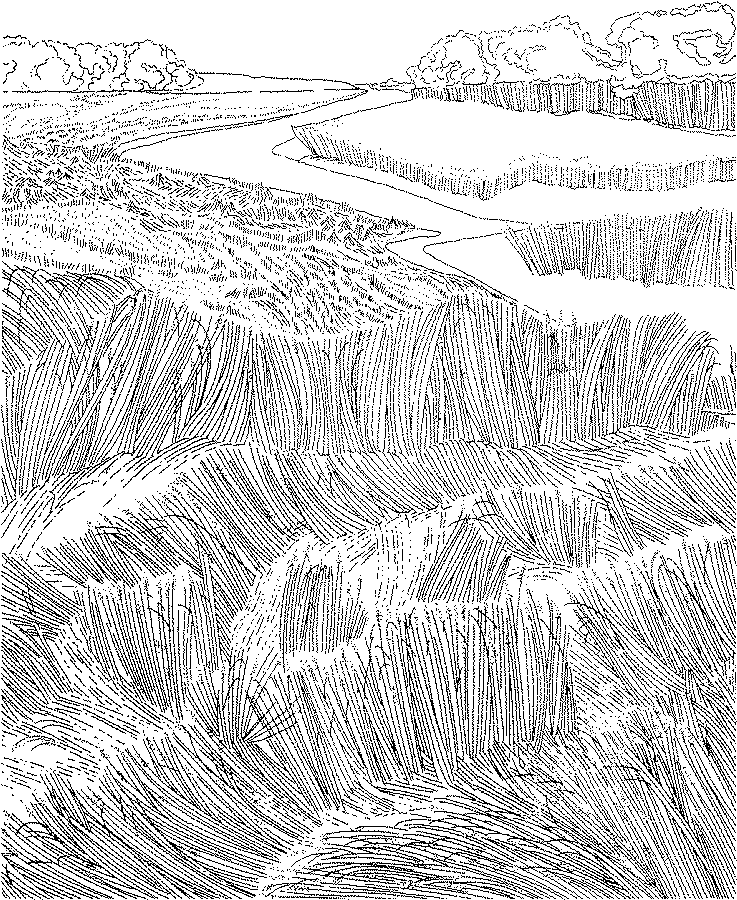

In the summer, everyone made hay, and it was a sight to see. Men and women descended upon the hills with scythes in hand, moving across the earth and under the hot sun until the grasses that once grew all the way to the boy's chest were reduced to stubble. When the hay was mowed, people gathered it and left it to dry in the barns and hayracks, tall wooden structures with roofs to keep the rain out. Before the mowing, Siegfried enjoyed climbing up an empty hayrack and looking out across the fields. For all its toil, the land was beautiful. In the distance, even beyond the ever-present castle, were the Pohorje and Haloze hills. When the flax bloomed, entire fields turned purple-blue and the wind passed over everything in great, rippling waves. In late summer, the sun alighted upon the swaying wheat and made what was yellow into gold. The Drava and its creeks cut through the landscape, babbling, heaving, sparkling. Its rushes lined the floors of every house, and its water laundered every cloth, washed every body, quenched every thirst, and was boiled in every pot.

When the boy went to Mass on Sunday, crowding with his peers and family in that tiny wooden chapel, Ewald the parish priest speaking in mysterious, droning Latin, of all the things Siegfried thanked God for, the two most important were the river and his mother. The Germans made a select few Slavs deacons and trained them in giving sermons in the vernacular, and, beyond the mores his family instilled in him and the stories they told about Jesus and His miracles, this was how the boy learned about God. The God from the sermons was wrathful and wary, omnipotent and omniscient, punished as much as He saved. Siegfried often found himself overwhelmed by the thought of and power of God. He felt God with him. When indecisive, he weighed his desires with what he thought God wanted. When he was punished or suffered, he believed that this was God's Will, that God created strife to test him, that the answers to his previously directionless questions could be explained by his actions relative to God's Word and expectation. Even if he was confused, he gained a sense that there would be an answer some day, at some point. When others had failed to do so, God taught him that all pain was useful pain.

As he grew older, Siegfried became steadier, more precise with his hands. He could be trusted with gentler tasks: collecting eggs, picking peas and beans, winnowing wheat from chaff. Around this age, he learned to reckon, to move numbers and things around in his mind. Reckoning was the only part of the toil that involved stopping, standing around, deliberating. How much have we sown? How much should we cut? How much is owed? How much will get us through the winter? How much wheat, how much chaff? And in reckoning, what existed became magically manipulated into what should be or must be or would be. Through reckoning, the future came to pass.

Siegfried watched adults doing this reckoning – counting aloud, using their fingers, doing sums – and, wanting to be useful, imitated them. After he joined his elders in the tasks of sowing, hand-reaping, and tying wheat into sheaves, the fieldwork became so grueling and dull, he escaped from the drudgery by trying to challenge himself, inventing more and more difficult sums and, once he got the hang of it, percentages to solve. This, for Siegfried, became a cherished activity even beyond the fields. When people fought in the house, when they screamed at each other, when everyone grew hungry and bitter in winter, when he was cold and miserable, when he had to help with the slaughter of pigs and chickens, he shut out the world. He partitioned the field and the harvest into ever more infinitesimal parts, visualized sheaves of wheat with precise numbers of stalks, separated them too, imagined them as flour and doled it all out. Everyone would have enough. Everyone would be full. His numerical world was governed by a logic of fairness the real one did not possess.

When Siegfried decided to show his family what he’d learned, his cousin Krešo beat him until he was black and blue, thinking the boy was cheating. You didn’t do those sums yourself. You heard someone else do them and now come to us with your false pride. No amount of protestation could change Krešo’s or anyone else’s mind. Shaking him by the shoulders, they asked Siegfried, "Who do you think you are? A boy pretending to the talents of a man? The devil's in you, I swear..." There it was again, that constant accusation, which he did not understand, that he thought himself better than others. Even though the more he worked, the more an uneasy truce settled over his relationships with adults and other children, people still said these things to him. People still called him a bastard. But how could he be? His mother had never married and therefore could never deceive. It never made sense to him, these questions of his existence. He asked his mother over and over, but she refused to say a word. "You are my son," she said, "My child. And that is enough."

Siegfried, despite his disappointment, let the matter go because he cherished his mother. He saw in her the two highest attributes: resolve and dignity. Honor despite slander. Hence, no matter how poorly people behaved towards him, he promised to act with dignity himself. Our rewards, his mother once said, will be reaped in the Kingdom of Heaven. How often he prayed that his mother would be loved more, and spared from derision and toil. His mother who loved him and took care of him, who asked so little of others, who bore the whole of everything on her own shoulders including the shame of having had him. These feelings and sentiments formed in Siegfried a precocious maturity. After a certain age, he rarely argued with his mother. Complained, whined, just like any other boy, but fought? Convinced by others that he was a burden, the boy did what he could to make his mother's life easier. Everyone worked, but Siegfried believed his mother worked harder than anyone else. Sometimes his mother worked with him. Sometimes she hauled water from the creek for the family, other times, at the castle, she hauled it from the well and stoked it under a fire during the months when the river froze. Sometimes she wove baskets and spun the wool she traded her laundress' earnings for, Siegfried on her lap until he could no longer fit there comfortably. Often she sang to him, stroking his hair until he fell asleep.

And in having him, Ajda lived not only for herself but for another. He kept her busy, brought her joy, made her question the world she had known all along merely because she had to guide another soul through it. What a marvel you are, she often thought, both awed and thankful that her son was born bright and agile, good-natured and strong. Sometimes, she even forgot about Sigismund and how the boy came into the world. This was partly because it seemed that, ever since the lord died, Sigismund had forgotten about her, too. One year, he was entirely gone, having traveled to Salzburg. Some business with the Archbishop. But every Shrove Tuesday, Ajda remembered the conversation between her and Sigismund before the boy was born. After a certain age the boy will be brought up the way I was brought up, trained the way I was trained. My son will be no peasant, and I prefer to have a bastard than no son at all. Every collection, she holed herself in the house with Siegfried, terrified that this would be the time when her son would be taken from her. And yet the years passed, one after the other, unchanged. The boy turned four, then five, then six, then seven, and now eight, and there was still no sign of the steward beyond his usual rounds. And because, for the time being, he served as castellan, even those duties were now usually delegated to other men. Not a singular steward, but a handful of accomplices.

But Sigismund had not changed. He was merely busy. In fact, he ran himself ragged, doing not only the work of the lord, but his own, too. The state of Pettau felt alarmingly fragile. The purpose of a lord, no one seemed to realize, was to serve as an intermediary between the estate and the rest of the world. Pettau's rest of the world involved a suzerain hundreds of miles away, a duchy to the north, and, right at her doorstep, a recently hostile kingdom. Information traveled slowly and there was no guarantee a messenger would make it either to his destination or back home. The negotiations with Hungary slowed things down, but neither Sigismund nor the archbishop believed that the Hungarians would stay peaceful for long. The sentiment was that they were looking for any excuse to restart the conflict all over again, especially because Pettau was weak. Beyond that, Sigismund did not have the knowledge Frederick did. He wasn't the one gallivanting up to Austria or Graz or Salzburg, the one at the Landtaiding in which regional affairs were decided and verdicts were read. The steward, being only a castellan, a ministerial of the Pettaus, not of the archbishop nor of the duke, was barred from participating in such things. Everything he heard, he heard secondhand. And all this distracted him from the matters he knew best: keeping track of arms, men, and goods.

He did not, however, forget about Ajda and Siegfried. No, every year, close to harvesttime, sometimes even donning his helm so that no one could recognize him, he saw his son. The steward saw his son stringing sheaves of wheat together with nimble fingers. He saw his son speaking a peasant language. He saw his son looking up at him with nothing but foreign, understandable loathing. And every time he saw this face which bore such resemblance to his own, it took all his resolve to pretend he did not recognize it. However, because others tauntingly pointed him out, his son was very much aware of who Sigismund was, if none the wiser regarding the truth behind his peers' accusations. And as for his mother, she had given him what Sigismund wanted in the form of the boy, and what he wanted from her, he knew she would never let him have. For a long time, this made him bitter. He forced himself to pass over the bridge without so much as a glance in her direction, all the while aware that his ignoring her made her happy. To his relief, much of this bitterness was alleviated by the sheer madness of his new role. But on the few occasions when he did see her, the same feelings stirred in him as always, as always. And one day, as he caught sight of her once more washing clothes by the river, he thought, why not? Why not have her come back up to the castle to see him? Just to speak a little while? Didn't he have a right to inquire about his own son?

*Those curious about the origins of this folkloric material can read notes on the subject at this weblog.